Since the first travel accounts of Morocco were made by Arab and European explorers during the Middle Ages the jewellery of North Africa has aroused great interest.

A plethora of ethnologists, during the colonial era made journeys, during which they gathered many fine examples to create the exhibits of the European museums, notedly those museums in France which have heavily documented collections of Jewellery which are classified in two Major groups; the Urban and the Rural.

The Urban jewellery presented a wealth of gold and precious metals which could be linked to the major Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilizations, the rural or Berber Jewellery as it became known, raised many questions as to it's origins and influences.

Many found a close connection with early antique Phoenician and Roman eras, others emphasized the huge technical input brought by different migrations (chiefly Andalucían post-requonquista ) but few could see the geographical evidence that the Berber, no matter what mystery encompasses their origin, should be approached as being part of the whole African continent.

The collection of Bert Flint in Marrakech along with his many years of studies whilst travelling in the Sahara and the Sahel conclude that the Berbers , in respect of beliefs and culture have more in common with Africa than was previously accepted.

The Berber people's travels through the Western Sahara bring many cultural aspects of West Africa into Morocco. For example, the weavings of the High Atlas tribes can be found in an almost identical style amongst the Fulani of the Sahel. Another example can be clearly demonstrated by considering the ubiquitous triangular Fibulas that have become the emblem of the Berber peoples. These should be read as the simplified form of the pre Islamic fertility frog symbol. A symbolism that is still in frequent use elsewhere in the arid parts of the continent.

This information illustrates that the Sahara acted as a sea, which was permanently crossed by ideas and influences, rather than as a barrier as previously perceived by geographers. This has remained as a continuous truth throughout time, striking evidence of this can be found within the study of jewellery and adornment.

The pictures below (which are gathered from the internet) of African peoples of different dates and origins all show a particular style of Jewellery which is worn on both sides of the Sahara.

These examples are made of gold but could have also occurred in silver or copper in Morocco as shown in different museums.

A gold disc from south east morocco, used as a bead in necklaces by jewish ladies. Kept in the “Musée du judaïsme marocain” in Brussels, Belgium.

"Qelnaq" necklace from south east Morocco, worn by jewish ladies. Kept in the “Musée du judaïsme marocain” in Brussels, Belgium.

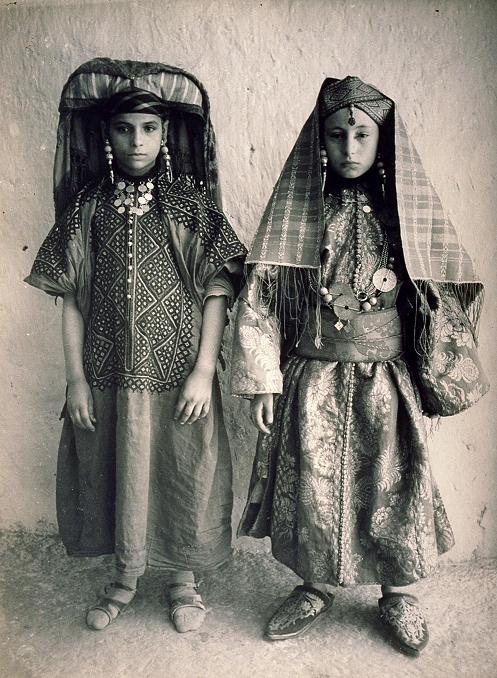

Two young newly-wed jewish girls from the tafilalet in south east morocco, the one to the right wears the “quelnaq” necklace with round discs

One can wonder how this design has been so popular in places separated from each other by thousands of kilometres?!

The first observation which is quite apparent is that these ornaments were worn very locally by communities that were a minority in their countries; Jewish in Morocco, Harratine (black skinned oasis dwellers in north Africa) in Libya and Songhai ladies in Mali. Furthermore we can note that these communities were located at both edges of the Sahara, the first two living in North Africa’s southernmost oases and the third in what can be considered as the most advanced post of a Sahelian community deep inside the Sahara desert on the riverbanks of the Niger.

This geographical location has played a major role in the destiny of the inhabitants of these places, giving them a great advantage by the creation of major trade hubs on the Saharan trade network. For instance Timbuktu was directly connected to both the Tafilalet and Ghadames through a chain of wells making It very easy to cross the arid landscape.

None of these groups participated directly in the transportation of the goods traded but were heavily involved in financing, commissioning and dispatching them.

We can certainly imagine the warehouses involved in such trade overflowing with ivory, ostrich feathers, salt, ebony, rhino horn but most importantly GOLD, the king of the kings!!

Gold was the most desirable of these goods, and was traded northward and into Spain. The gold was mined in the south close to the Gulf of Guinea in the Animist territories. Gold was so important in the local economy of North Africa that the Kingdom of Morocco which was then under the SAADI dynasty rule, waged a war on the Songhai empire in the late 16th century, defeating, occupying and eventually taking the total control over the gold trade in North West Africa by installing a allied state in Timbuktu

Gold was mainly powder straight from the mines and transported northwards in sacks carried by camels. One must also note that beside the mined gold, a steady trickle of gold artifacts were also exported.

No wonder people who were involved in a very deep commercial relationship would eventually end up sharing many cultural aspects: Gifts, cross marriages and cultural emulation could have led people to adopt new-on-the market jewellery.

We should then try to understand why these three groups have adopted this jewellery separately from all other groups and regions? Gold elements are widespread in the traditional adornment of the rich areas of the sahel and all the north Saharan oases that were involved at one time or another in the trasaharan trade, but none witnessed this jewelry element beside the Timbuktu, Tafilalet and Ghadames.

The fact that south of the Sahara only Songhai women wear it is a strong clue that it originates in the region of Niger valley around Timbuktu or at least it was from there that it began to reach the two locations further north.

Ghadames merchants were among the most powerful in the city of Timbuktu and their African descent would have enticed them to intermarry with local high ranked women and bring them back in their home country where these ladies would keep this jewellery among their style of adornment. They have not only retained the jewellery but also the way to use it : A head ornament.

At the opposite side, Jewish merchants of Tafilalet weren’t able to intermarry and could only use the jewel as a gift to their wives or as part of the imported gold to be later traded once in Morocco. The fact is that Jewish ladies wear it as part of a necklace (i.e. gold bead) means that the jewel was only imported as a raw material devoid of any cultural meaning, transformed from a head ornament to a bead!

The Tafilalet and Ghadames were the main commercial hubs in North Africa, they were also Timbuktu’s biggest commercial partners. The Souss valley further to the west in South Morocco was rather connected to Senegal river through central Mauritania, while Libya shared a lot of its trade with the haussa people in north Nigeria/South Niger, therefore even if we find gold elements in these regions, the gold disc remains absent.

This trade was not only spreading the use of the goods but also, people, ideas and culture. A whole civilization network

This is one of the many examples were sub-Saharan Africa has exported one of its cultural aspects to the northern part of the continent, following a multi-millenia history of exchanges dating back to when the Sahara was still an evergreen savannah!!!

The French colonization and the earlier Atlantic trade has made this Transaharan network to dwindle rapidly until it completely disappeared.

Now the borders between Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Mali are closed and only crossed for illegal trade and smuggling.

All these countries have turned their back to the Sahara and are now looking to the seas and globalization, thus leading to the total extinction of cross borders influences and the demise of those that have been built in past time.

In both Timbuktu and Ghadames, this jewel is still used but only worn in festive occasions or by artists keen to revive the tradition, while in morocco the discs completely disappeared when the Jews of the south east left the country, only some loose beads have survived, employed by merchants in making new necklaces and leading to a new sand-cast production.

Replies

Very good idee to let more people enjoy the trip through North Africa.

Thank you for all the praises, please note that Sarah have been of a very greaat help to correct my words, it is very challenging to bring out my text in English as i tend to think in French: she had done a wonderful work

IF Sarah finds it worth of publishing then it is an honor for me

With Permision from Alaa Eddine I will be delighted to publish this article..

S X

I`m just waiting for the book!!!

Alaa eddine Sagid,

What a writer you are. So colorful. I can taste the atmosphere,color and liveliness of your article. Will go through it again. The funny thing is that only through the replies of this discussion did I see your article. Thank you.

Gr. Ingrid.

this should go in the new magazine, its perfect for it!

Hi Alaa eddinne Sagid, How nice of you to form your thoughts and experience about ethnic jewellery into an written essay. I fully agree that trade routes are of great influence on knowledge,technics and fashion. It is brought in, local craftsmen start copying them and adding some of their own to it or leave it out and than it is adopted as a local happening. Well done. I enjoyed reading it.

Gr. Ingrid.

Wonderful story,thanks!

I have a necklace of those beads.I only new they were Jewish beads from Morocco

Wonderful article thank you! My husband is Songhai, and many Songhai (or Sonrai) who live in Tuareg cities like Timbuktu and Gao, wear less gold but silver like the Tuareg. One can say, it is mixed, some wear gold (not real one), others prefer silver. Perhaps because some Sonrai have mixed with Tuareg (we have some in my husbands family in Gao and the south of Mali, they belong to the Kidal Tuareg (Kel Iforas). Also the Peul (Fulani) people of Mali like Gold (e.g the huge twisted earrings). The Sonrai had a huge kingdom in Mali, with the capital of Gao, the famous graves of the Askia Kings in Gao belongs today to the world heritage of UNESCO, (actually it is a mosque, looking similar like the ancient mosques of Timbuktu). Timbuktu has indeed a lot of influence from Morocco (e.g. the wooden doors with the metal parts on them), and from Mauritania. It is a very fascinating city and well worth to study its history....

Beautiful photos!!! WIll read it in peace, as soon as I have enough time and nobody to disturb me!

-

1

-

2

of 2 Next