Chapter 3

Sir Robert Ho Tung was the grand old man of Hong Kong. Macau’s most important library was named after him. The Sir Robert Ho Tung Library at 3 Largo de Santo Agostinho might be a good place for Pedro to begin his research. Pedro loved the library’s yellow façade, punctuated by black arched windows. He loved the lush garden around it, but something was wrong with the front door. “I will enter through the side!” Pedro thought, walking around the corner.

The small, arched door Pedro found looked nondescript, and its rusty hinges played loud, atonal creeks when he opened it. Inside, the room appeared unvisited. Shades of sunlight through the window illuminated dust particles in the air. Piercing the silence, a ghostly voice said, “Welcome to the Chinese Ancient Books Chamber.”

She was an ancient, skeletal figure with a bob haircut and thick, black, round glasses. “I am looking for information about jade in Hongshan culture, but I don’t read Chinese. Do you have anything in Portuguese?” he asked.

“Yes. This way, please.”

The dust of ages superseded the air. ‘This woman is 2000 years old,’ he thought. ‘I’m just an interior designer.’ Pedro was getting nervous. “Why is the room like this?” he asked his new companion.

“Jade eclipses the tallest of men,” she said.

Choosing curiosity over his reluctance to follow her into the depths of the room, Pedro walked into the narrow hallway: a maze of bookshelves reaching to the ceiling. “How would I get to the top shelf without multiple ladders?” he asked. The librarian didn’t answer. She just led him around corners.

They passed rows and rows of bamboo scrolls. They felt smooth as Pedro touched them. The different visual designs of their calligraphy intrigued him. Some characters were drawn like thick blocks; others were wild. One he held up.

“Who wrote this scroll?” he asked the librarian. She glanced at it briefly, “My husband, Dr. Chang. I didn’t think any of his manuscripts were still in here.” She grabbed it and turned her head so quickly, Pedro sensed her heart had skipped a beat. ‘Something tragic happened here,’ he thought, but then his attention was drawn back to the scrolls.

He was intrigued with the vertical logic of the writing. He had seen the same thing in the layout of Chinese houses and the placement of objects in jade pendants.

As they continued to walk, it occurred to him that as Westerners were taught to think “outside the box,” the Chinese thought “inside the box.” The discipline of thinking within parameters made their solutions astonishing. On nearby shelves, elaborate binders were stacked horizontally. He passed by the Analects of Confucius, but saw nothing about jade, and nothing in Portuguese.

“Where is the other side of this room?” Pedro asked, getting claustrophobic. “Oh, the corners never end,” the librarian responded. A crescent of red lipstick formed slowly above her wrinkled chin. Realizing she had to be bothered by conversation, she waved her hand upward. “We have over 5000 volumes of rare Chinese texts — historical, phantasmagorical books.” Her eyes lit up. “The Chamber is a maze in the ancient Chinese tradition. No one who has walked in here has ever gotten out. They got lost instead.

“Excuse me?” Pedro raised his voice.

Paying no attention to him, she quoted, “As one grows older, hope becomes hard to hold onto. One loses the energy of delusion. One forgets about returning home.” “Mi Fu said that.” She turned back to look at Pedro. “Mi Fu? The Northern Song Dynasty calligrapher? He was called the wild scholar of Shenyang. The Emperor said he was someone society always needed one of, but could not afford two of. Ha!” Pedro’s face was intense, but empty.

She huffed, turned around, and kept walking. Then he heard a door open, and she was gone. Where was this door?

He was in the middle of a thousand untraveled hallways with no idea of the overall pattern of the room.

‘I’m dreaming. There was opium in the street food, and I’m laying in a stupor at the back of an alley,’ thought Pedro, looking about him. ‘No, I’m really here. I’m going to die of starvation after having found the ultimate wisdom in a rare book, and no one will ever know.’ Suddenly, Pedro was startled by a coin dropping to the floor, and forgot his impending doom.

“Hello?” He went toward the sound, and found a book about jade written in Portuguese. “Ah!” He opened it to a random page. “Hongshan jades have profound simplicity in aesthtiecs, whereas Liangzhu jades have technical supremacy. The best Liangzhu birds’ eyes have a concave surface, which curves inwards from the edge to the iris, forming a small depression.” [9]

Photograph: Incised grey nephrite jade bird. Liangzhu Culture. Lau Legacy Malaysia Collection.

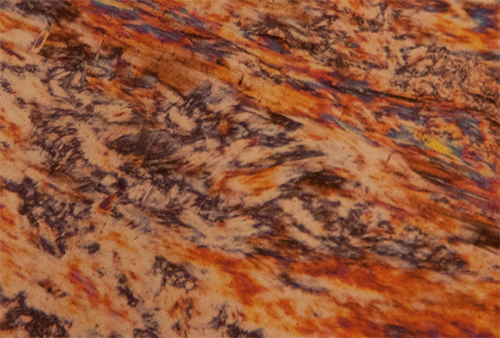

Pedro flipped to the beginning and saw a picture of the chemical composition of nephrite for the first time. “Nephrite jade is made up of tremolite and aconite, two members of a group of complex silicate minerals known as amphiboles. Their existence is a result of metamorphosis. A magnesium-rich rock must have a river of magma run through it and experience high pressure. That changes the crystals into needle-like shapes. When the crystals merge and achieve a 4:1 ratio of magnesium to iron, nephrite deposits form.” (1)

Photograph: Optical photomicrograph of nephrite jade, showing the fine, fibrous texture. Cross-polarized light. Width of field, 1.3 mm.

Flipping the page again, “Hongshan societies existed between 4500 and 2500 BC and were located in the Liao and Daling river valleys in northeast China. Elaborate platform burials at Niuheliang, consisted of central burial crypts and smaller slab graves called cist tombs. These contained offerings almost exclusively of small jade objects. An absence of utilitarian objects made the case that Hongshan society valued religion over wealth.” (2)

Photograph: Area of the archeological site Niuheliang, Liaoning Province, taken by Jessica Rawson. “Chinese Jade: From the Neolithic to the Qing,” page 30.

Photograph: Photograph: Cist tomb at Niuheliang, taken by Jessica Rawson. “Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing,” page 31.

Hongshan culture had no writing, only tomb identifications. Pedro figured these jades defined the power relationships between people. ‘But how will I ever know?’ He wondered. He wandered until he fell over a skeleton. It sat on the floor, back up against a bookshelf, posed, with a copy of the Quan Tangshi, a complete collection of the poetry of the Tang Dynasty. Pedro couldn’t help but look at the skeleton more closely. Its finger was pointing to the left. The skull was topless, with a distorted front jaw, as if the tongue had been pulled from it. “He talked too much so his tongue fell out,” an unknown voice explained dryly. Pedro quickly turned his head. “It looks like it was pulled out! Who are you? Where are you? How many more skeletons are in here?”

Replies